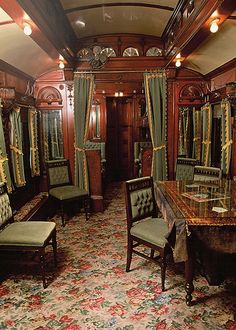

Forever Free is an immersive, anthology opera that enacts an imaginary meeting of the outrageous, queer Scottish-American opera mega-star Mary Garden with African-American soprano, Sissieretta Jones, known as “the greatest singer of her race” and Aida Overton Walker, the Queen of the Cakewalk. Set in the women’s private Pullman train cars during an overnight trip from New York City to Chicago in 1913, this encounter explores issues of race, sexuality, and power in an era of racist terror. A chorus of Pullman Porters testifies to the significance of the encounter as the three divas sing, dance, seduce, and challenge each other.

The performance will take place on a train trip from New York City to Chicago, a journey that took 20 hours in 1913, and currently takes 19 hours. The piece will unfold over a 24-hour period beginning on the train platform in New York and ending on the platform in Chicago, with performances at stops along the route as well as in several cars on the train. Audiences and community members will participate in the performance as fellow passengers and porters.

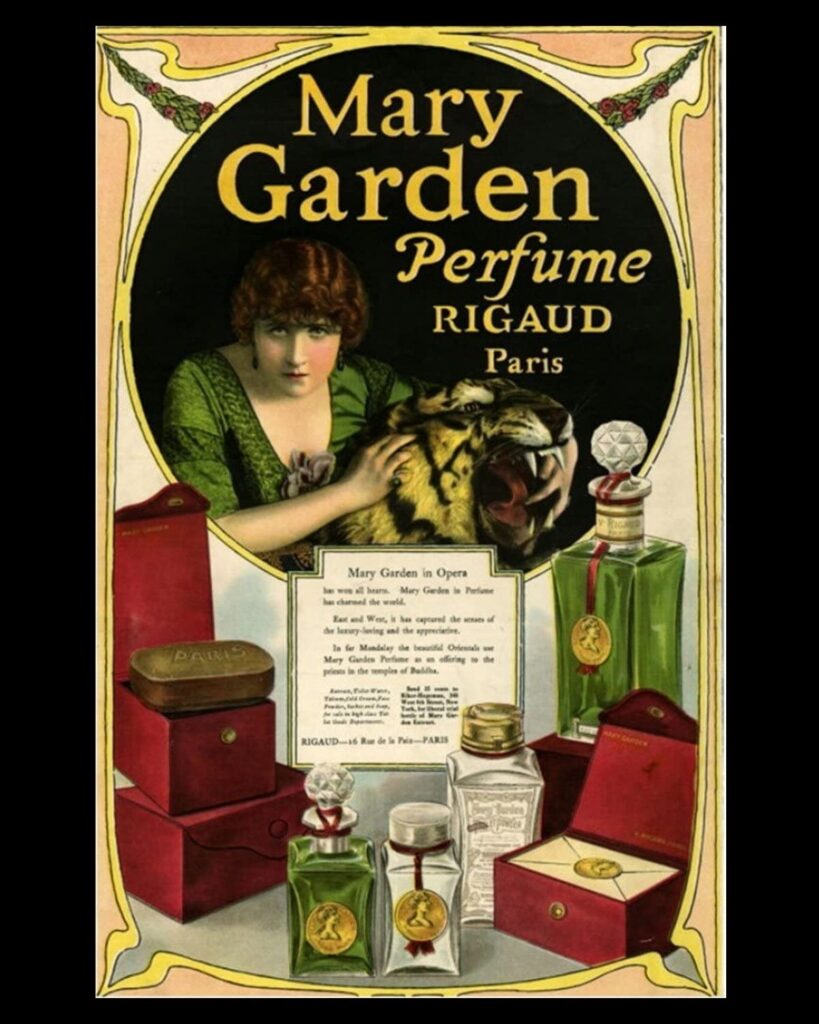

Mary Garden was infamous for her depiction of powerful, erotic women from Salome to Thaïs, as she created and inspired roles in fin-de-siecle opera by such composers as Debussy and Massenet. For the first half of the 20th Century, Garden’s scandalous stage performances, off-stage love affairs, diva antics, and war-time heroism were covered extensively in major newspapers, including the New York Times and the Chicago Tribune. She bankrupted the Chicago Opera Association when she served as artistic director in 1921, pronouncing the million-dollar deficit for her productions “worth it.”

In in her autobiography, she confesses to trysts with famous male composers and conductors, but her admiration and companionship are reserved for other women. She claims to have been tricked into serving as the spokesperson for a popular perfume, signing a contract when she thought she was signing an autograph. She observes that the “Negro porters” with whom she traveled on her private Pullman car referred to her not as a famous opera star, but as “the Perfume Lady.”

Sissieretta Jones, who was excluded from the grand opera stage due to racism, nevertheless performed arias and scenes in recital for world leaders in the US, the Caribbean, and Europe and for an adoring public at venues such as Madison Square Garden and Carnegie Hall. As the director of the Black Patti Troubadours, she became the highest paid African-American performer of her time and she also owned a private Pullman car, allowing her to avoid the humiliation of racist segregation when she traveled. Her 40-plus-member troupe performed dance, acrobatics, minstrel songs, spirituals, and opera scenes. Jones’ signature song was a classical rendition of the minstrel staple, “Old Folks at Home (Suwanee River)” by Stephen Foster. She was celebrated for her renditions of the aria “Sempre Libera” (Always Free) from Verdi’s La Traviata, Gounod’s “Ave Maria,” and Rossini’s Stabat Mater. Presenting minstrelsy and spirituals with grand opera, Jones re-contextualized all of these works in a repertoire that resisted racist violence.

Aida Overton Walker began her career as a dancer in Jones’ troupe, where she met and married minstrel star, George Walker and his performing partner, Bert Williams. The trio set up their own troupe and when George Walker passed away, Overton Walker took over her late husband’s roles in drag. She was known as the Queen of the Cakewalk and taught the dance to wealthy, white patrons in private lessons. Like Garden, Overton Walker was infamous for her own rendition of the Salome dance. Like Jones, she established her own troupe and earned independence as a black woman producer.

As an all-male, all-African-American workforce, the Pullman Porters played a critical role in the early civil rights movement. Establishing an important core of the black middle class in the United States, the porters organized for equitable labor laws and carried African American newspapers and news of racial injustice from station to station to African American communities across the country.

On this imaginary train ride, the three divas make their way to Chicago in September 1913, shortly after the murder of two men in rural Illinois that is part of a decades-long campaign of racist terror across the United States aimed at subjugating African Americans.[i] The travelers are unaware of this incident as they board the train in New York, and the first act of the opera takes place during the afternoon and evening, as the porters chorus giddily observes their famous passengers with a revised version of the “Neighbors’ Chorus” from Offenbach’s opera, La jolie perfumeuse (The Pretty Perfume Lady). When the porters recognize Aida Overton Walker on her arrival, they break into a Cake Walk inspired by her choreography from the play Dahomey (1903) to escort her to her train car.

The three divas settle into their respective cars, Sissieretta sings her signature song, Stephen Foster’s “Old Folks at Home”as she unpacks and Mary sings the Thaïs aria, “Tell Me that I’m Beautiful,” to her mirror. The three meet up in Mary’s car to entertain and outdo each other by singing selections from their repertoire. To pass time, Aida reads Tarot cards and the women sing the Card Trio from Carmen, which presages Aida’s premature death in 1914. To lift spirits, Mary challenges Aida to a Salome dance off, set to the dance sequence from Strauss’s opera, Salome. The act ends with the three women trading vocal runs in an arrangement of “Sempre Libera” (Always Free) from La Traviata, led by Sissieretta.

The second act unfolds at night as Sissieretta returns to her car and sings Gounod’s “Ave Maria” before going to sleep. The night porters stay up gossiping and shining shoes. Two featured porters have a own romantic moment, singing the duet from Bizet’s The Pearlfishers, about two devotees who glimpse the goddess they worship, then take each other’s hand and promise eternal friendship. Meanwhile, Mary and Aida have a tryst in the guise of Salome and Delilah, with Aida singing Delilah’s seduction aria from Saint-Saëns’ Samson and Delilah, “Mon Coeur s’ouvre à ta voix” (My heart opens to your voice) and Mary singing Salome’s aria, “Ah, I have kissed your lips.”

The mood shifts in the third act, just before dawn, as news of the lynching in Illinois makes it to the morning porters as they pick up a copy of the Chicago Daily Conservator, an African American newspaper from porters coming from Chicago during a stop outside Cleveland. The porters sing a mournful version of “Old Folks at Home” as they spread the news. Blissfully unaware, Aida and Mary get ready to sleep the day away in their separate cars, with Mary singing “Despuis le jour” (After the day) the famous aria about a woman’s joy after a night of love from her breakout role in Charpentier’s Louise. The porters deliver a copy of the paper to Sissieretta, who is up early. Devastated by the news, she sings the soprano aria from Rossini’s Stabat Mater, backed by the Porter Chorus.

This initial storyline will evolve with the contributions of collaborating artists and community members. Celeste Landeros will serve as originating producer and librettist, establishing a collective of artists who will collaborate on an evolving set of performances. As an anthology opera, the piece draws from existing, public domain repertoire that was performed historically by the three divas of the turn of the 20th Century, along with additional repertoire from the period suitable to the story. The classical repertoire is the most immediately accessible, but further research will lead to the inclusion of material from Overton Walker’s musical productions, as well as African American spirituals and Scottish folk song.

Additional librettists may write dialogue for the characters between songs that will be set to music by contemporary composers, who may also create additional music if so inspired. Choreographers will develop movement for the divas’ dance sequences as well as for the Porter Chorus, drawing from historical references and contemporary movement vocabularies. Visual artists will contribute as set designers and may create multi-media installations within the train cars. Given the length of the performance and depending on the number of train cars available, there may be multiple casts of the principal roles. Performers will improvise on the core material in response to the participation of community and audience members at the time of performance.

The development of the piece over several years will allow for fundraising and the establishment of partnerships with Amtrak or with a private touring company that offers travel on vintage trains. The artistic development will include the creation of stand-alone solo opera-cabaret shows featuring each of the three divas as well as chamber opera performances of scenes from the opera on stage and on stationary train cars and adjacent platforms. The development will also include engagement with community organizations in New York, Chicago, and Miami. Documentary and narrative audio and video recordings will be produced at all stages of project development.

The culminating performance(s) on the New York-to-Chicago train ride will be the centerpiece of a festival of performances along the route celebrating opera that is openly queer, feminist, and features Black, Asian, Middle Eastern, and Latinx artists as performers and creative collaborators. This festival may include presentations of independent projects inspired by the principal historical figures, such as Call Her by Her Name!, the Sissierretta Jones project initiated by the late Jessye Norman, as well as reconstructions of any of the musical plays produced by Aida Overton Walker. The festival will also welcome thematically unrelated queer, feminist, and people-of-color opera projects.

[i] See “Posse Fatally Wounds Negro,” Daily Illinois State Register (Springfield), September 13, 1913; “Negro is Killed by Posse,” Belleville News Democrat, September 13, 1913. In his classic volume, Ralph Ginzburg included the Tamms incident in his list of Illinois lynchings and suggested that two black men had been killed: “Two Unknown Negroes, Tamms, September 12, 1913.” See Ralph Ginzburg, 100 Years of Lynchings (Baltimore: Black Classic Press, 1988), 260.